Foreword

…Ever since the Peace of Westphalia we have rationalised the nation state as the supreme entity of governance. Each state has its own geographic boundaries, identity, culture, language, and sovereignty over its domestic affairs and territories. But situations evolve – sometimes dramatically, and at other times incrementally. Even the most ardent advocate of national sovereignty has to admit that the state has a limited capacity to govern in a world where the biggest challenges we face – from climate change to health inequalities – do not respect boundaries…

For this reason, governance should be understood as a collective effort. Decision-making is not the sole purview of the government, the civil service, academia, media, civil society or corporations. It is a collective endeavour. Once we admit this we can begin to address the challenges of transnational governance…

OPSI and the MBRCGI are the very definition of transnational cooperation, and this report is a vital outcome of their partnership. It does not underestimate the challenges of cross-border governance; instead, it provides a level-headed assessment without over-rationalisation or drama. It is, in short, essential reading.

See print report for full foreword

Former Prime Minister, Finance Minister and Foreign Minister of Finland (2008-16). He is currently Professor and Director at the School of Transnational Governance at the European University Institute in Florence.

Introduction

Issues facing governments are increasingly complex and transboundary in nature, making existing governance mechanisms unsuitable for managing them. Governments are leveraging new governance structures and mechanisms to connect and collaborate in order to tackle issues that cut across borders. Governance arrangements with innovative elements can act as enablers of cross-border government collaboration and assist in making it more systemic.

This work has led to the identification of three leading governance approaches and associated case studies, as discussed below.

Theme 1

Building cross-border governance bodies

Government organisations are typically structured to focus on narrow subject domains. However, complex issues or those spanning the remit of multiple jurisdiction require rethinking existing governance mechanisms and structures. To address this, governments are creating new governance bodies to manage issues that span borders. They vary in their level of formality, legal mandate, scope and architecture, but their objective remains the same: to co-ordinate and harness the collective efforts of actors divided by borders.

The efforts identified through this work find that governments are engaging with innovative governance bodies at transnational levels to tackle global issues, as well as at intranational levels to ensure coherence domestically.

Case Study

Kvarken Council

A Nordic cross-border co-operation body composed of representatives from sub-national governments in Finland and Sweden. Its mission is to leverage the power of cross-border collaboration to stimulate growth and innovation in the Kvarken region and to strengthen the area’s international competitiveness, internal connectivity and attractiveness for foreign visitors and investors. Guided by the belief that trust-based collaboration among all actors in the region can lead to great results, the Council aims to involve even the smallest municipalities in its projects so as to stimulate inclusive and environmentally sound economic growth.

Theme 2

Innovative networks tackling cross-border collaboration

Cross-border government innovation can be driven by top-down or centre-out governance bodies, but can also emerge peer-to-peer connections through horizontal networks. Indeed, the complexity of cross-border areas may render formal institutions too cumbersome, or the barriers to direct institutional collaborations may be too great, thereby increasing the value of other forms of day-to-day collaboration. Networks are becoming more innovative in their form and function, and as a means for developing innovation capacities across borders and systems – while simultaneously fostering cultural capacities that reinforce cross-border collaboration.

Case Study

Open European Dialogue (OED)

An informal network that brings together European members of parliaments from across the political spectrum to discuss common policy issues and challenges. Focusing on human-centered process design and open dialogue, the OED provides an innovative space for cross-border dialogue that strives to be diverse, informal and apolitical. Politicians from different levels of government, parties and countries can discuss many different topics, test their views, build personal relationships and be confronted with a range of opinions.

Theme 3

Exploring emerging governance system dynamics

A “system” in this context can be defined as elements linked together by dynamics that produce an effect, create a whole new system or influence its elements. Changing these dynamics requires a new way of examining problems and bold decision making that fundamentally challenges government institutions and governance structures.

At present, governance bodies usually take the form of top-down entities. Networks work to build horizontal capacity. However, conceive of their individual members in traditional terms. Emerging dynamics of governance systems are working to pioneer more holistic approaches, many of which re-envision the nature and role of major players and build new connective tissue and mechanisms to innovate together. Examples of such approaches include co-designing, co-funding and co-governance of initiatives across borders.

Case Study

Borderlands Inclusive Growth Deal

An innovative governance system that is intentional, systemic and collaborative in its approach to partnerships, as well as investment, planning and delivery. It represents a transformational opportunity to achieve long-term sustainable prosperity for people, places and businesses within the Borderland regions along England and Scotland within the United Kingdom. It has amassed joint funding of GBP 450 million (EUR 520 million) as an integrated investment package for cross-border projects related to improving physical spaces and skills in the region.

Findings

Unpacking findings and lessons

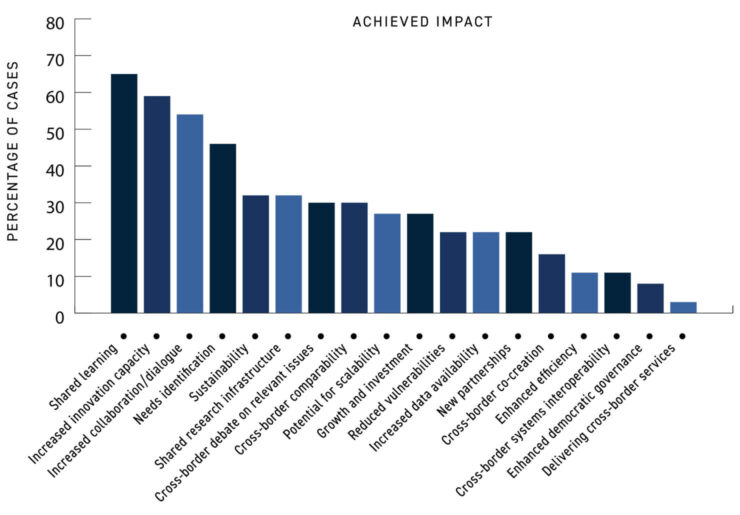

This work has surfaces a number of benefits, challenges, and success factors related to cross-border government innovation.

Key benefits to cross-border collaboration include regulatory effectiveness, economic and administrative efficiency, managing risks across borders, enhancing knowledge flow and bringing about economies of scale. For innovation projects, governance bodies set collective visions and objectives, and align components to address major challenges and implement global missions. Networks bring people together to disseminate knowledge and innovation methods across borders and to serve in a sensemaking capacity for participant inputs. Innovative systems dynamics such as co-funding and co-governance function as connective tissue to drive continuous alignment. The Call for Innovations cases identify additional benefits.

Core challenges that limit cross-border collaboration include additional layers of co-ordination, difficulty of jurisdictions deviating from norms, perceived loss of sovereignty, fully understanding the costs/benefits of cross-border collaboration, competing political interests, and gaining a sense of equity in the distribution of the costs and benefits. Specific to innovation initiatives, challenges also include:

- Understanding the impacts and benefits of the cross-border efforts.

- Obtaining funding.

- Navigating administrative boundaries and different frameworks.

- Understanding and addressing mutual needs.

- Securing political leadership and stakeholder buy-in.

- Building trust.

- Lack of a strategy to guide collective efforts

- Differences in culture and ways of working.

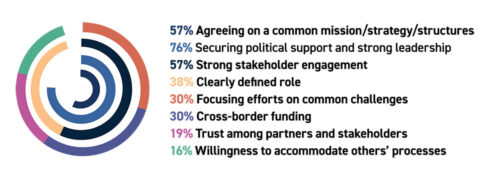

A number of success factors underpin success examples. For broad cross-border collaboration, focusing on science-driven irrefutable facts, areas that involve global “goods” and global threats, and issues where there is a strong incentive for co-operation helps greatly. As does developing concrete objectives. Defining common missions, strategies and goals is also critical. The existence of a co-funded secretariat to carry out work is also of great value. Finally, trust serves as a foundational success factor. The Call for Innovations cases also cited a number of success factors

Recommendations

Five key recommendations have been identified for governing cross-border challenges:

- Secure political and leadership commitment and advocacy from the highest levels of government. This is critical for achieving priority status, influencing decision making, building confidence, gaining momentum, securing funding and ensuring that the necessary support and innovative structures are in place for sustainable and successful initiatives.

- Pursue cross-border efforts only where these make sense and involve all stakeholders in establishing a clear vision and strategy for cross-border collaboration. The pursuit of cross-border efforts should only be undertaken when a challenge can be better addressed collectively than individually, and when incentives to collaborate already exist or can be put in place. Once such areas are identified, all partners should agree collectively on a vision and strategy with concrete objectives.

- Ensure structural enablers are in place and explore relevant systems dynamics that can better connect partners and collectively guide work. Consider putting in place elements like tailored governance bodies to facilitate vision and strategy development, and dedicated teams to carry out the work, in order to allow for a systems-wide approach. Explore new systems dynamics (e.g. co-funding, collaborative governance, joint services) to facilitate joint action.

- Share costs and benefits related to collaboration, and be aware that benefits may take time to be realised and may not be distributed equally. Cross-border government innovation efforts should involve give and take from all partners, albeit with an understanding that the latter may take time to emerge and may be unevenly distributed. The goal should be a net benefit for all partners when compared with the costs of not collaborating.

- Be a good partner and build trust by fostering strong relationships over time. Cross-border government innovation involves building mutual understanding, sharing power and decision-making, being transparent about motives and expectations, and being willing to accept and work within the structures and processes of other partners. Governments need to invest time in fostering sustained relationships.

Download Print Report

Governing Cross-Border Challenges